The Economics of Burnout: How Overwork Leads to Diminishing Returns

Within today’s high-pressure work and academic environments in the United States, both employees and students often face pressures to work longer hours, prioritizing output over well-being. Many people glorify working long hours, often seen as a badge of honor. However, this culture of overworking oneself is not just harmful to our health, but is also a fundamental economic inefficiency. Burnout is more than a personal problem — it represents a significant economic challenge because it slowly diminishes human capital and reduces long-term productivity. Working longer hours consistently overlaps with one simple yet essential economic principle: diminishing marginal returns. In economics, the concept of diminishing marginal returns explains that beyond a certain point, each additional hour of input produces less output, eventually leading to negative productivity. This means chronic overwork leads to long-term losses in human capital. Empirical evidence supports this claim: studies confirm that a 1% increase in working time yields only a 0.9% increase in output for call center agents (Collewet & Sauermann, 2017), while academic staff with high emotional exhaustion show absenteeism rates 3.3 times higher and presenteeism rates 4.7 times higher than their peers (Amer et al., 2022). Rest is not the same as idleness; it is a productive recovery process.

The Mechanism: Burnout

Burnout, which is characterized by symptoms of exhaustion, cynicism, and a reduced sense of accomplishment, directly impairs the cognitive and emotional capacities required for high-quality work. A meta-analysis of over 100,000 students (Madigan & Curran, 2021) found a strong negative relationship between burnout and academic achievements. The feeling of "reduced efficacy" showed the strongest correlation to poorer grades. Exhaustion and cynicism were also consistently predicted to cause lower performance (Madigan & Curran, 2021). Overwork causes lower scores because burnout depletes the cognitive resources needed to succeed and function efficiently. Reaching a level of burnout leads to diminished academic performance and impaired cognitive functions like problem-solving and attention (May et al., 2015).

Evidence of Diminishing Returns: More Hours, Less Output

Empirical evidence from the service sector data, particularly a study on the daily number of hours worked on workers’ productivity from a call center in the Netherlands from mid-2008 to the first week of 2010, shows diminishing returns. This confirms that economic theory on diminishing marginal returns predicts that after a certain point, additional working hours produce progressively less output. A study of call center agents found that as their effective working hours increased, their productivity, which was measured by the number of calls handled, decreased. The results of this study show moderately decreasing returns to hours worked. They found that for every 1% increase in working time, there was only a 0.9% increase in output (Collewet & Sauermann, 2017). This fatigue effect takes place even in a job with mostly part-time workers.

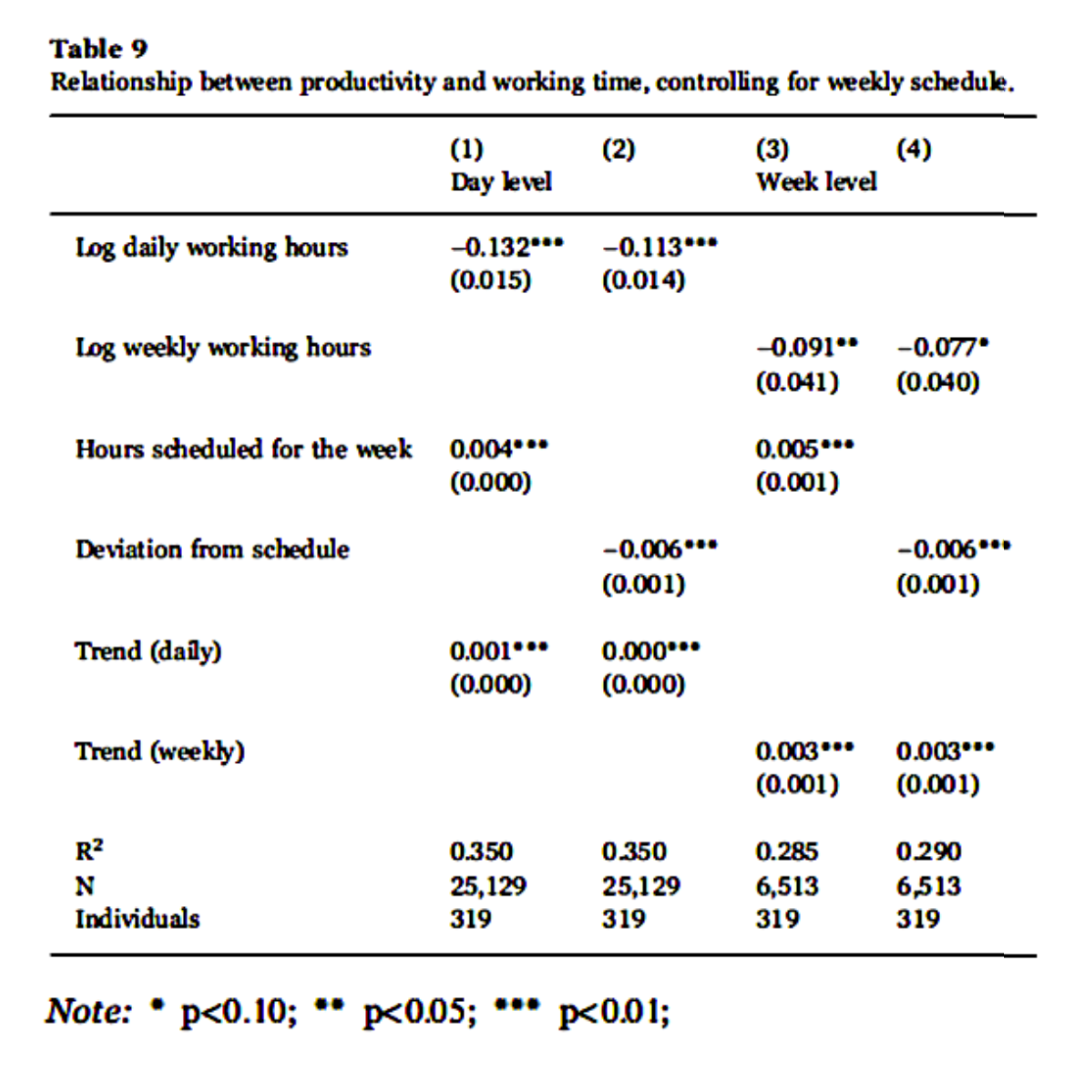

Table 1: Relationship Between Productivity and Working Time, Controlling for Weekly Schedule (Collewet & Sauermann, 2017)

The table above, from the call center study, presents regression results confirming the statistically significant negative relationship between logged working hours and productivity. Broader economic analysis supports this, suggesting the optimal workday is around eight hours, with evidence showing a 10% increase in overtime can reduce output by 2–4% (Dolton, n.d.).

Productivity Loss Across Sectors

Overworking also translates directly into a loss of productivity in the workplace. A study conducted in 2024, consisting of over 1,700 Portuguese employees, found that 49.9% reported at least one burnout symptom, with exhaustion being the most intense and frequent complaint. This does not just represent personal feelings of being tired — the study was able to quantify exhaustion as a measurable predictor of performance decline (Gaspar et al., 2024).

A survey of academic staff likewise found that the emotional exhaustion aspect of burnout was overwhelmingly effective at predicting productivity loss. Staff with high emotional exhaustion levels had significantly more absenteeism, seeing rates up to 3.3 times higher. Burnout also affected presenteeism rates, defined as being at work but mentally disengaged, which were 4.7 times higher for burned-out employees than their less-burnt-out colleagues (Amer et al., 2022).

Additionally, a 2025 study of Korean workers found that over-extension of work hours led to burnout and thus mediated approximately 51% of the total effect of occupational stress on health-related productivity loss (Kim et al., 2025).

These studies underscore that ignoring burnout is not just a personal issue; at the organizational and national level, it reduces overall efficiency, increases absenteeism, and creates long-term economic costs. Although working more hours may initially appear to increase output, this research suggests that reducing excessive hours and incorporating recovery periods actually improves long-term productivity and cognitive performance.

The Long-Term Economic Impacts

The cost of burnout isn't confined to a bad semester or a failed exam—it can permanently damage your productivity. The lifelong cost of overworking is seen through a 2025 study from Sweden, which quantified it as "economic scarring." Two years after a clinical burnout diagnosis, individuals suffered a permanent 12.36% earnings loss, highlighting that overwork can cause lasting economic and personal damage, reducing quality of life and economic resilience.

This damage is not just personal but also affects those around us. The same study found that the toll of worker burnout spills over to families, reducing spousal earnings and negatively affecting children's educational outcomes. When aggregated to a national level, the study estimated that the presence of burnout reduces national labor income by 3.6% through a combination of sick leave, individual earnings losses, and these family consequence spillovers. This is a massive inefficiency that ends up draining the system and reducing economic prosperity.

Conclusion

The myth that "more hours equals more output" is economically illiterate. Evidence from various industries and nations tells a consistent story: that overwork leads to burnout, which in turn diminishes productivity in the short term and inflicts lasting economic damage in the long term. The best strategy for individuals and organizations is to recognize the value of human capital and understand it as a resource that depletes without proper maintenance. On the individual level, it is important to prevent burnout by setting reasonable work or study hours and creating a supportive social environment, including strong personal and professional relationships. Sustainable performance requires recognizing that rest is not the enemy of productivity but its essential partner; organizations that integrate regular breaks, reasonable work hours, and supportive environments see long-term gains in efficiency and employee well-being.

Edited by Caitlin Williams

References

Amer, S. A. A. M., Elotla, S. F., Ameen, A. E., Shah, J., & Fouad, A. M. (2022). Occupational burnout and productivity loss: A cross-sectional study among academic university staff. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 861674. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/public-health/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2022.861674/full

Collewet, M., & Sauermann, J. (2017). Working hours and productivity. Labour Economics, 47, 96–106. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0927537117300603

Dolton, P. (n.d.). Working hours: Past, present, and future. IZA World of Labor.https://wol.iza.org/articles/working-hours-past-present-and-future/long

Gaspar, T., Botelho-Guedes, F., Cerqueira, A., Baban, A., Rus, C., & Gaspar-Matos, M. (2024). Burnout as a multidimensional phenomenon: How can workplaces be healthy environments? Journal of Public Health. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10389-024-02223-0

Kim, E., Kim, H.-R., Choi, S.-J., Cho, H.-A., Cho, S.-S., & Kang, M.-Y. (2025). The mediating role of burnout in the association between occupational stress and health-related productivity loss. Industrial Health. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40484685/

Madigan, D. J., & Curran, T. (2021). Does burnout affect academic achievement? A meta-analysis of over 100,000 students. Educational Psychology Review, 33, 387–417.

May, R. W., Bauer, K. N., & Fincham, F. D. (2015). School burnout: Diminished academic and cognitive performance. Learning and Individual Differences, 42, 126–131.

Nekoei, A., Sigurdsson, J., & Wehr, D. (2025). The economic burden of burnout (Discussion Paper DP19091). Centre for Economic Policy Research. https://ideas.repec.org/p/cpr/ceprdp/19091.html

Kafka, F. (2022). The metamorphosis (Kindle ed.) [Book cover]. Colossal Publishing. https://www.goodreads.com