The Green Gentrification of the Atlanta BeltLine

The conversion of Atlanta’s old rail lines into a combination of parks and trails has been celebrated as one of the nation’s biggest urban renewal projects. To observers, the BeltLine seems to demonstrate that a metropolis can recast its industrial past as a story of sustainability and connection. However, the very project that was set out to unite Atlanta has strengthened its existing fissures. What began as an effort to bring together segregated neighborhoods has instead driven up property values and displaced thousands of long-time African-American residents. The BeltLine’s story reveals how projects marketed as “sustainable” are often still driven by economic pressures that favor growth, creating outcomes that undercut their stated goals. The logic of progress, pursued without consideration toward equity, ends up reproducing the disparities it originally promised to heal.

Atlanta’s geography still bears the marks of racial hierarchy. The rail lines that comprise the BeltLine once demarcated the boundaries of redlined districts, separating black and white neighborhoods. When the city adopted Ryan Gravel’s 1999 proposal to convert those tracks into parks and transit, it sold the project as a renewal that would attempt to right those wrongs. In renderings and public vows, officials talked about inclusion and shared prosperity, as if the rhetoric alone could erase history’s line. However, capital followed its familiar course. Investment first spread toward the Eastside, where white homeowners held sway and business activity grew, while the largely Black Westside was left waiting for promises that came late. In a few years, rental rates along the Eastside Trail surged by 43 percent, and new developments meant to revitalize instead redefined who could afford to belong (Margolies, 2025).

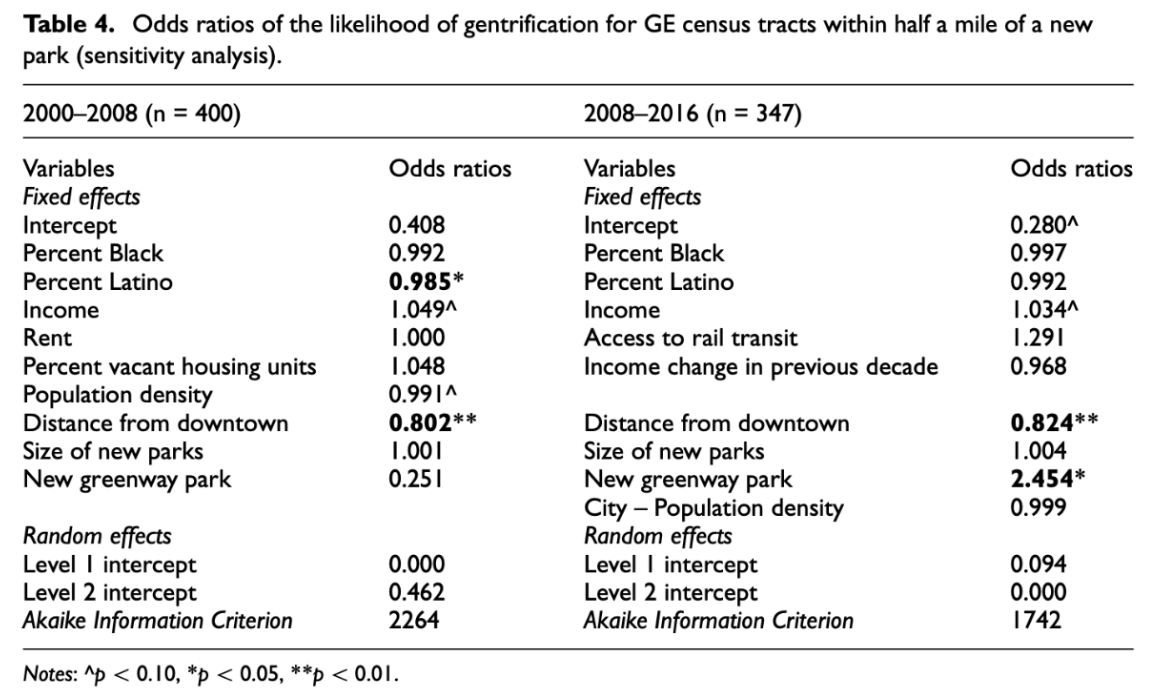

This process, known as green gentrification, occurs when the development of new parks and green spaces leads to social displacement. As Rigolon and Nemeth explain, the establishment of new parks in historically disinvested neighborhoods often leads to housing price increases and the displacement of low-income residents (Rigolon & Nemeth, 2020). Their study of ten U.S. cities found that neighborhoods within a half-mile radius of newly built greenway parks between 2008 and 2016 were 2.454 times more likely to gentrify than comparable areas without such projects (see Figure 1). Being close to downtown areas amplifies this effect, as parks near business districts are the strongest drivers.

This logic is simple. A new park enhances the surrounding neighborhood, causing home prices to rise. Those who cannot keep up with these costs are pushed out. Without policies protecting current residents, the environmental upgrade ultimately becomes a transfer of wealth.

Supporters of the BeltLine often argue that, while regrettable, displacement is an inevitable effect of progress. They cite the trees planted, the trails extended, and the billions of tax revenue as proof of success. That line of reasoning confuses what can be quantified with what’s fair. According to Immergluck and Balan, housing values have risen between 17.9 percent and 26.6 percent more for homes within a half-mile of the Beltline than for the rest of the city (Immergluck & Balan, 2017). That jump underscores how the project’s modest strides in housing have failed to prevent investor-driven price spikes. Once the market re-prices a neighborhood, retroactive safeguards become symbolic gestures. A family displaced cannot later return. A community, once torn apart, cannot reassemble. In that sense, The BeltLine doesn’t prove that green revitalization and equity can’t coexist, but that without structural and social safety nets, so-called sustainability becomes another instrument of exclusion.

Policies to make the growth from the BeltLine more equitable broke down amid political compromise. The Tax Allocation District, envisioned as a financing tool for housing along the BeltLine, has currently fallen short of its mandate. By 2023, only 3,555 of the 5,600 promised affordable units have been completed (Okotie-Oyekan, 2023). Furthermore, even as the District pulled in upwards of $9 billion in development, the portion set aside for affordable housing remained negligible with just 63% of these promised units having been delivered (Margolies, 2025). In the early stages, money set aside for the project went to infrastructure and marketing rather than land acquisition, which triggered investment that drove up surrounding property values. Those same rising prices later made it even harder for the city to acquire land for affordable housing, effectively locking the project into the very shortage it was meant to prevent.

The city’s inclusionary-zoning ordinance, enacted in 2017, required that ten to fifteen percent of new units be priced below market rate (City of Atlanta, Department of City Planning, 2017). However, developers had the option to fulfill this obligation through paying an in-lieu fee, a loophole that left housing near the BeltLine out of reach. Many developers paid the surcharge to sidestep embedding units in high-end projects, as the fee was markedly cheaper than lowering rents for 15% of their units. By conflating equity with growth, city officials portrayed renewal as an absolute positive, assuming that rising prosperity would help all. Yet their willingness to allow the in-lieu fee loophole meant that the policy ultimately intensified the displacement it was meant to address, leaving vulnerable communities unprotected.

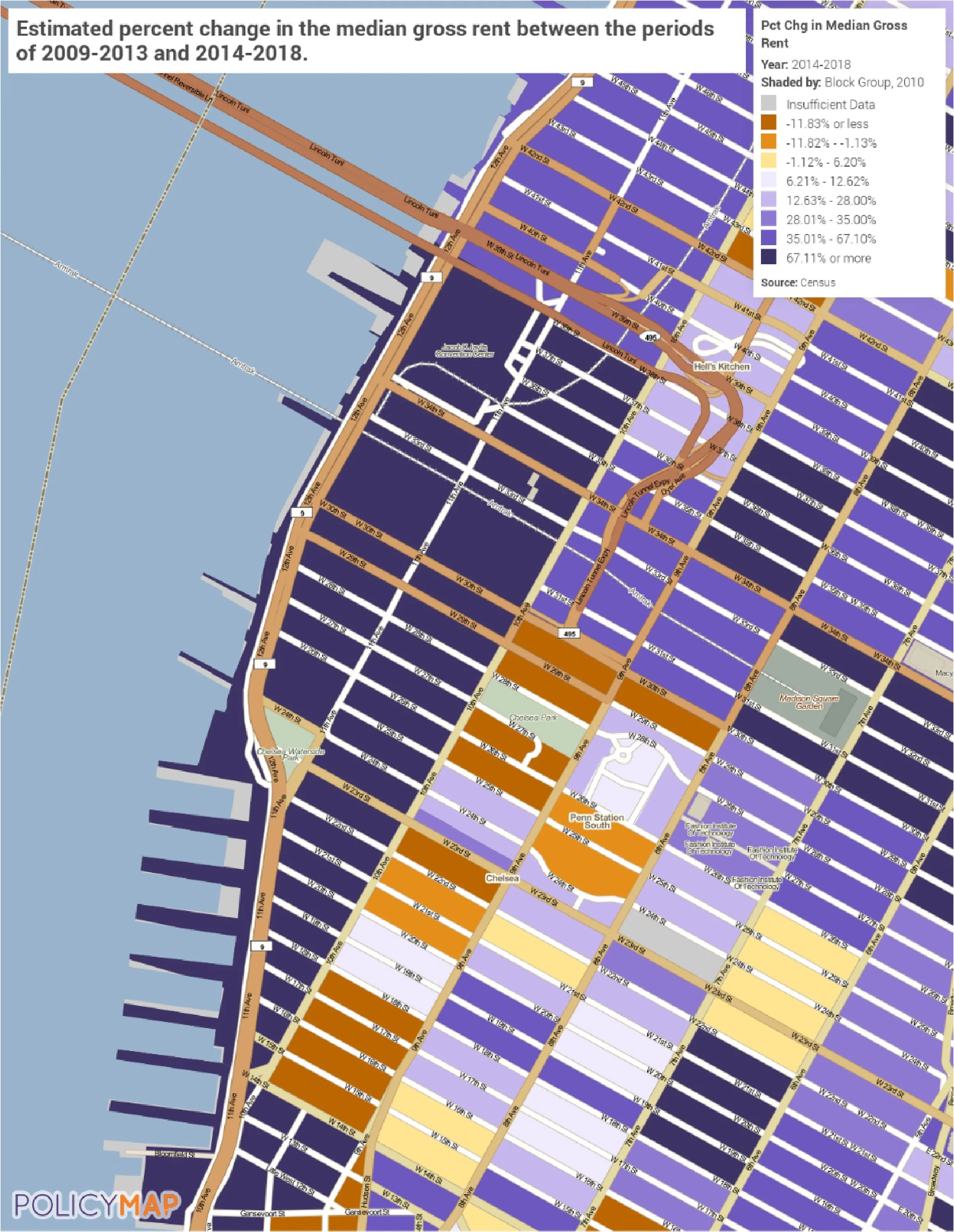

The BeltLine’s reimagining of an industrial rail into a trail mirrors New York’s High Line. A quasi-experimental study of the High Line that combined GIS analysis with a difference-in-difference framework found that homes located within 80 meters of the park commanded a 35.3% price premium, with the steepest gains at the elevation level of the structure (Black & Richards, 2020). Moreover, median rents in the vicinity of the Line rose by 68% during the first post-opening period (see Figure 2).

Atlanta’s BeltLine exhibits the same tendencies. Rents along the Eastside Trail have increased by more than half and adjacent parcels are currently being revalued for development. In each case, the rhetoric of walkability and community masks a situation in which the premium attached to upgrades is priced into land, and the people who can’t shoulder that cost end up being displaced.

The claim is not that sustainability-driven projects can’t bring renewal but that under today’s conditions, they seldom do. Genuine revitalization, by contrast, should be judged by its durability, not its profit margin. That calls for deliberate integration of environmental planning and housing policy. For example, setting aside land adjacent to forthcoming parks for affordable housing units, instituting tax freezes, and offering low-interest repair loans that allow long-standing residents to stay put. When green investment proceeds without such protections, it becomes another vehicle for exclusion. The BeltLine demonstrates that cities must treat green infrastructure as both environmental and social capital. When the value nature returns is held in trust for the neighborhoods that endured decline, renewal can become inclusive.

Edited by Caitlin Williams

References

Anguelovski, I., Connolly, J. J. T., Pearsall, H., & Masip, L. (2019). Why green “climate gentrification” threatens poor and vulnerable populations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 116(52), 26139–26143. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26897069.

Black, K. J., & Richards, M. (2020). Eco-gentrification and who benefits from urban green amenities: NYC’s High Line. Landscape and Urban Planning, 204, 103900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103900.

City of Atlanta, Department of Planning. (n.d.). Housing compliance. City of Atlanta. https://www.atlantaga.gov/government/departments/city-planning/housing/housing-compliance.

Immergluck, D., & Balan, T. (2018). Sustainable for whom? Green urban development, environmental gentrification, and the Atlanta BeltLine. Urban Geography, 39(4), 546–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2017.1360041.

Margolies, J. (2025, Sept 2). It was supposed to connect segregated neighborhoods. Did it gentrify them instead? The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/09/02/business/atlanta-beltline-success-displacement.html.

Rigolon, A., & Németh, J. (2020). Green gentrification or “just green enough”: Do park location, size, and function affect whether a place gentrifies or not? Urban Studies, 57(2), 402–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019849380.

Estimated percent change in the median gross rent between 2009–2013 and 2014–2018.

Note. From Eco-gentrification and who benefits from urban green amenities: NYC’s High Line, by K. J. Black & M. Richards, 2020, Landscape and Urban Planning, 204, Article 103900 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103900). Copyright 2020 Elsevier.