How Do Reproductive Health Clinics in Georgia Stay Financially Viable Amid Policy and Social Change?

Since the overturning of Roe v. Wade, 66 abortion clinics across 15 southern states have been forced to close, leaving just 13 operating clinics all located in the state of Georgia (Kirstein, Dreweke, Jones, and Philbin, 2022). As a result, Atlanta has become a hub for abortion services; women from surrounding southern states such as Alabama, Mississippi, and Tennessee travel to Atlanta for the sole purpose of receiving essential abortion services. While abortion healthcare centers function primarily by offering abortion services, reproductive healthcare clinics offer a broad spectrum of services, including miscarriage management, STI testing, prenatal care, and limited abortion services. Several abortion-focused clinics, such as the Feminist Center for Reproductive Liberation (FCRL) in Atlanta, Georgia, operate within the general framework of reproductive healthcare centers to remain financially sustainable. However, under Georgia’s recent passing of the Georgia’s House Bill 481 (Georgia General Assembly, 2019), clinics in Georgia can only legally offer abortions under specific circumstances and within tight gestational time frames. These constraints leave Georgia’s abortion clinics in a state of uncertainty: how do they balance high demand with increasingly restrictive laws? How are these centers able to stay financially sustainable amidst shifting funding challenges and policy change? This article argues that to remain financially viable amidst changing policy and social pressures, Georgia's reproductive healthcare clinics must broaden their services and diversify their revenue. They can achieve this by expanding their range of non-abortion healthcare services, investing in virtual and telehealth infrastructure, and more effectively integrating with local and municipal funding programs.

On January 22nd, 1973, the Supreme Court of the United States deemed state regulation of abortion healthcare unconstitutional in the case of Roe v. Wade (The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2025). SCOTUS ruled that abortion restriction violated an individual’s right to privacy and therefore infringed on the 14th amendment’s Due Process Clause. The ruling asserted that a state could not restrict an individual from obtaining an abortion during their first or second trimester; the state could, however, prohibit abortions after the start of the third trimester. After this ruling, the supply of abortion healthcare clinics increased throughout the United States, a key example being the Feminist Center for Reproductive Liberation (FCRL) an abortion-focused clinic within the broader reproductive healthcare landscape which opened in 1976. Due to this decreased barrier to entry and increased supply, abortion clinics were able to accommodate a higher quantity of patients seeking abortion care. These factors allowed abortion centers, such as FCRL, to survive financially; although they still relied on mostly private funding, they were able to legally offer services which allowed them to remain financially sustainable.

To sustain a stable revenue, abortion clinics rely on their plethora of donations and medical grants to provide medical services. Clinics like the FCRL offer an array of reproductive services including (limited) abortion healthcare, miscarriage management, STI testing, and postpartum care. Further, abortion clinics rely on donations and grants from organizations such as Access Reproductive Care Southeast (Access Reproductive Care-Southeast, 2025). This stream of revenue is used to support centers’ key expenses such as medical supplies, staff incomes, security, and legal compliances. As I discuss later in the article, newly introduced reproductive legislation forces reproductive organizations to limit their services which threatens their financial viability.

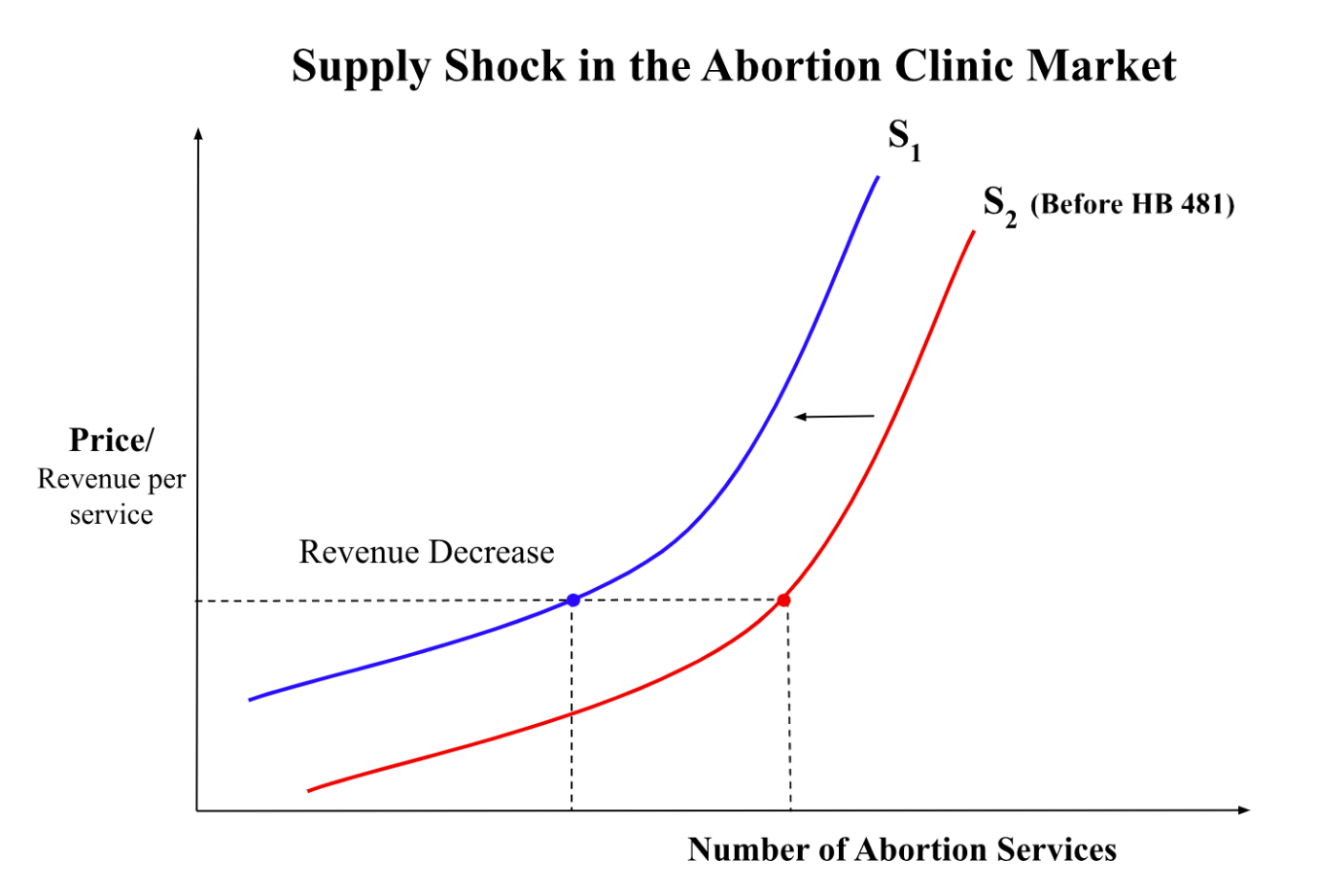

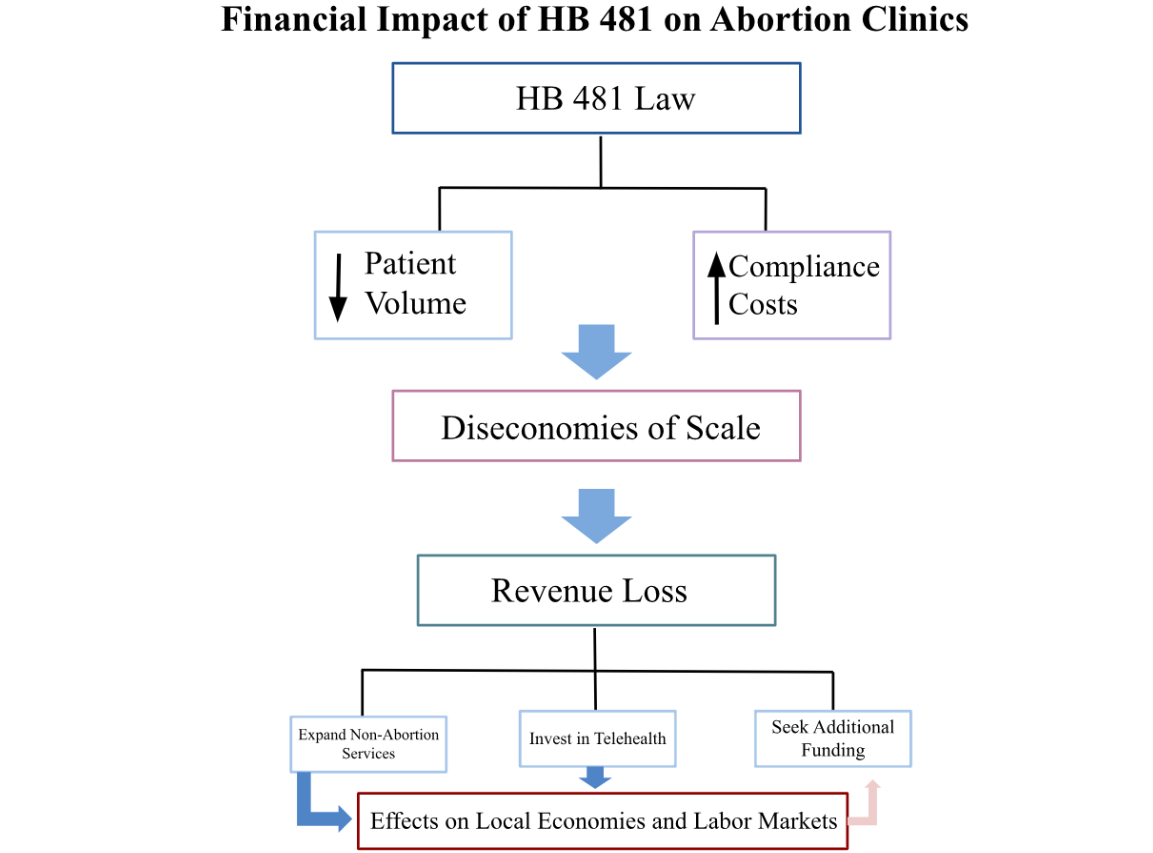

The enactment of Georgia’s House Bill 481 (HB 481) (Georgia General Assembly, 2019) in 2019, also known as the Heartbeat Bill 481, has served as a significant policy shock for abortion healthcare clinics. HB 481 was not able to effectively go into law until the Supreme Court of the United States overturned Roe V. Wade which eliminated a federal standard to protect abortion rights on a state level (Abortion Is Legal in Georgia, n.d.). This new legislation effectively bans the provision of abortions past six weeks of pregnancy, when a heart beat can typically be detected in fetuses. Because of HB 481, certain abortion clinics such as the Feminist Women’s Health Center in Dekalb County are forced to “turn away an average of five to seven patients every day” (Mador, 2023). Studies show that nearly 90% of prior abortions performed before HB 481 would no longer qualify under the law since they occurred after six weeks of pregnancy (Redd et al., 2023). This restriction of legally authorized services acts as a negative supply shock for the abortion clinic market which contracts the market for abortion care. This contraction reduces total revenue for clinics across Georgia and forces them to rely on donations (since they can no longer rely on revenue directly from services).

However, abortion clinics nationwide have been struggling to secure adequate funding for their clinics due to a shift in the abortion policy landscape. For example, Planned Parenthood of Northern New England has reported a “funding shortfall of about $8.6 million” over the next several years (Davis, 2024). Other clinics, such as the Planned Parenthood of Greater New York, announced that due to financial struggles, they will not provide abortion services beyond 20 weeks. The National Abortion Federation (NAF) reported that they partially funded 60,000 abortions within the first half of 2024; however, they had to reduce patient grants from 50% to 30% of the cost of care due to funding shortfalls (Mosley-Morris and Resnick, 2024). Reductions in total revenue coupled with significant decreases in donation revenue have forced clinics to take alternative strategies to remain financially viable.

To strategically adjust to new legislation and protect financial stability in Georgia, clinics have diversified their revenue stream and sought alternative means of funding. For example, clinics such as FCRL have expanded their range of services; they now provide perinatal care and are hoping to build infrastructure to progress research pertaining to reproductive healthcare (Feminist Center for Reproductive Liberation, 2025). Further, clinics have expanded their means of communication to include telehealth visits. By doing so, they aim to reduce the operational costs that are associated with in person visits, see a higher quantity of patients, and hopefully offset lost revenue. Lastly, although most clinics still struggle to obtain necessary funding, abortion clinics in Dekalb County, Georgia, have become the first clinics in Georgia to receive funding from their local government to fund their local reproductive healthcare centers (Feminist Center for Reproductive Liberation, 2025). While this funding does not directly combat the financial effects of HB 481, it is still able to ease the financial burden of many Dekalb clinics. By diversifying services, adopting Telehealth, and cutting their levels of operation, clinics have been able to mitigate the negative supply shock that has occurred due to recent legislation and remain financially viable among the shrinking reproductive health market.

Economically, HB 481 acts as a negative supply shock for Georgia’s abortion clinic market which disrupts the flow of revenue and forces abortion clinics to strategically adjust their sources of income. Particularly for smaller clinics, decreased patient volumes coupled with increased compliance costs creates diseconomies of scale. To offset these losses, clinics have expanded their service offerings to generate alternative income; these adjustments illustrate how policy restrictions redirect financial incentives. They push clinics towards investing in cost cutting technologies and remote care. Overall, these financial adjustments demonstrate how reproductive policy restrictions ripple through labor markets, local economies, and the healthcare market. Looking ahead, abortion clinics in Georgia are likely to continue expanding non-abortion services, invest further in telehealth infrastructure, and pursue additional private and municipal funding opportunities to maintain financial stability. These strategies will allow clinics to adapt to ongoing policy restrictions and continue serving patients in a rapidly changing reproductive healthcare landscape.

References

Abortion Is Legal in Georgia. (No Date). 2019 abortion law. Retrieved from https://www.abortionislegalingeorgia.com/2019-abortion-law

Access Reproductive Care–Southeast. (2025). Supporting people in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Tennessee. National Network of Abortion Funds. https://abortionfunds.org/fund/access-reproductive-care-southeast/

Davis, E. (2024). Local Planned Parenthood offices warn of multi-million dollar deficit, call for state funding. Maine Morning Star. https://mainemorningstar.com/briefs/planned-parenthood-of-northern-new-england-projects-multi-million-dollar-deficit-calls-for-state-funding/

Feminist Center for Reproductive Liberation. (2025). 49‑year‑old reproductive health organization Feminist Center unveils bold new brand reflecting liberatory vision for the future. https://feministcenter.org/press/49‑year‑old‑reproductive‑health‑organization‑feminist‑center‑unveils‑bold‑new‑brand‑reflecting‑liberatory‑vision‑for‑the‑future/

Feminist Center for Reproductive Liberation. (2025). DeKalb County becomes the first county in Georgia to allocate money towards reproductive healthcare. https://feministcenter.org/press/dekalb-county-becomes-the-first-county-in-georgia-to-allocate-money-towards-reproductive-healthcare/

Georgia General Assembly. (2019). House Bill 481 (154th Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess.) – Full text. https://www.legis.ga.gov/api/legislation/document/20192020/187013

Kirstein, M., Dreweke, J., Jones, R. K., & Philbin, J. (2022). 100 days post-Roe: At least 66 clinics across 15 U.S. states have stopped offering abortion care. Guttmacher Institute. https://www.guttmacher.org/2022/10/100-days-post-roe-least-66-clinics-across-15-us-states-have-stopped-offering-abortion-care

Mador, J. (2023). Awaiting court action on 6‑week ban, Georgia abortion clinics turn patients away. WABE. https://www.wabe.org/awaiting-court-action-on-6-week-ban-georgia-abortion-clinics-turn-patients-away

Mooseley‑Morris, K., & Resnick, S. (2024). “Perfect storm” of crises is leading to cutbacks in abortion care, advocates say. Georgia Recorder. https://www.georgiarecorder.com/2024/08/15/perfect-storm-of-crises-is-leading-to-cutbacks-in-abortion-care-advocates-say/

Redd, S. K., Mosley, E. A., Narasimhan, S., Newton-Levinson, A., AbiSamra, R., Cwiak, C., Hall, K. S., Hartwig, S. A., Pringle, J., & Rice, W. S. (2023). Estimation of multiyear consequences for abortion access in Georgia under a law limiting abortion to early pregnancy. JAMA Network Open, 6(3), e231598. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.1598

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2025). Roe v. Wade. Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/Roe-v-Wade

Pointer, A. (nd). The Feminist Women’s Health Center in Atlanta, which has been providing abortions three days a week, recently added a fourth day despite Georgia’s six-week abortion ban [Photograph]. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/us-news/six-week-abortion-ban-florida-c5f00f7e